A plan for the economy

An essay by Andrew Sissons and John Springford, November 2025

Andrew Sissons is an economist and policy advisor who has spent much of his career working for the UK government, and the rest of it trying to influence government from the outside. He has worked on a number of different policy areas, including climate change, energy, innovation and local growth. He is writing in a personal capacity. His Bluesky account is here.

John Springford is an economist. He works on Britain and Europe in the global economy, especially on trade, productivity, migration and energy. He is an associate fellow at the Centre for European Reform. He is also writing in a personal capacity. His Bluesky account is here.

Press coverage – Heather Stewart, The Guardian | Mehreen Khan, The Times | Alphaville, Financial Times | Jonathan Freedland, The Guardian | Martin Wolf, Financial Times | Brian Feeney, Irish News | Polly Toynbee, The Guardian

Summary

The UK is in a hole. Wages have barely risen in seventeen years, and the public realm is fraying. Its politics are increasingly fractious as a result. Added to this are a raft of new challenges – tackling climate change and completing the switch to clean energy, higher defence spending, a growing demand for public services as society ages – that must be addressed. But these problems are all fixable, with consistent action.

A sober analysis of what’s gone wrong is needed. In the essay that follows, we try to produce one, and to chart a way forward. The central theme is that Britain hasn’t based its economic strategy on the things it is good at. As a result, it has too few big companies located around the country that raise wages and spending locally, leading to virtuous spirals in which skilled people get sucked in and local small businesses enjoy more demand and their workers receive higher wages.

It has strengths in tradeable services, such as finance, law, accounting, consulting, media, video games and university education; but many of these industries are concentrated in London and the south-east – the region of the country that is as rich as the top-performing places internationally. Even there productivity has stagnated and investment has been weak since the vote to leave the EU in 2016.

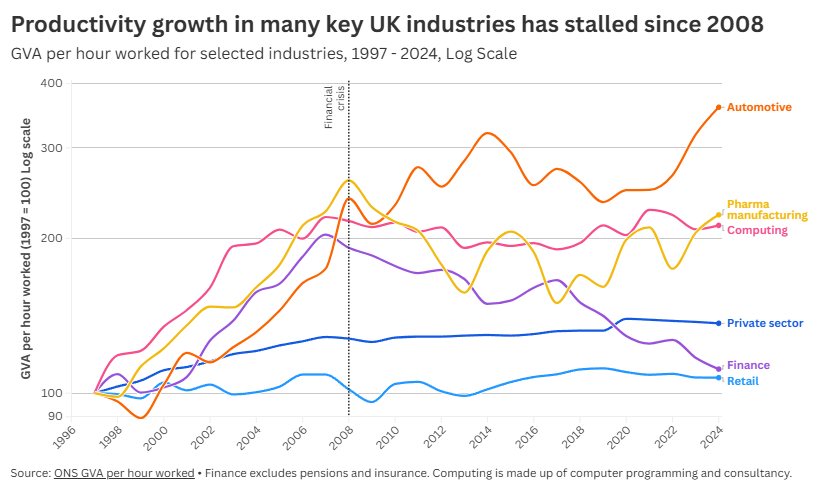

Manufacturing output has been very weak since the global financial crisis. But it continues to be an important anchor for many regions outside the major cities. Brexit has also badly damaged the sector, with value-added declining rapidly since the UK left the single market and customs union in 2021.

Aside from the shocks of the financial crisis and Brexit, Britain has failed to reshape its second-tier cities enough to suit its comparative advantages. As a result, many have weak economies. These cities are not dense enough, and have limited road and public transport. That means their effective size is too small to provide the range of skilled people that knowledge economies, which focus on tradeable services, need. Redundant buildings and land are not brought back into use rapidly enough: many cities still have pockets of derelict land near their centres.

Energy costs are high, largely because of Britain’s reliance on gas, but also because the costs of upgrading the energy system remain high. As we set out, reversing or slowing down the net zero programme will not solve the problem. Higher European gas prices mean that more gas-powered plants will not lower bills. Nuclear is expensive, because it is a capital-intensive form of generation, like wind and solar power, and interest rates have risen, pushing up the cost of capital. The only realistic way forward is to complete the switch to clean energy while efficiently managing the cost of investment this entails.

Inflation in the services sector has been high in recent years. And even before the Great Inflation of 2022-4, the UK has tended to be a relatively inflationary economy compared to its peers. That indicates an infrastructure and competition policy that is not working as well as it could. Much of this problem is in utilities and transport, which are congested. Successive governments have not provided the regulatory pressure for investment in more capacity, or undertaken the investment directly. But there are also signs that the competition regime for services that require contracts – personal finance, consumer energy and telecoms, for example – is failing to keep bills down. This spending is gobbled up by companies in the form of a producer surplus, where more consumer-friendly markets would allow them to spend on other goods and services, raising the efficiency of the economy.

The tax system provides weak incentives for businesses to expand. The threshold for self-employed people to start paying VAT is high, encouraging them to stay being relatively unproductive sole-traders rather than joining together in larger firms. Property taxation discourages people from moving – literally taxing them for doing so, in the case of stamp duty – which inhibits the movement of people from less to more productive areas. In some cases, the government has made things worse – making hiring costlier by raising employer national insurance contributions, for example.

Future challenges make fixing the problems harder. Fiscal space must be made for investment to deal with Britain’s congested infrastructure, and to raise defence spending, given the threat from Russia and the US retreat from defending Europe. While spending control remains important, it is hard to see big cuts to public spending, because ageing societies demand more health and social care, and richer societies need more education – especially if, like Britain, their model is founded on human capital.

So what can be done? We set out a programme of reform:

- Repair Britain’s position in Europe’s manufacturing base. It is not clear that either the UK or the EU want rejoin, but a much better deal is possible. Participation in the single market for industrial goods would reduce trade costs significantly, and bring higher investment in the manufacturing sector. This would help smaller cities and towns that rely on it. The price would be free movement of people and fiscal contributions to other EU member-states. But free movement would help to provide skilled, younger workers that are needed to curb the costs of ageing. And the big jump in free movement after the 2004 enlargement is unlikely to be repeated for many years, as it will take time for Ukraine to join and poorer existing member-states have become markedly richer.

- Make it easier for knowledge workers to immigrate. Net migration is falling rapidly after the post-pandemic boom, which was also seen in other rich countries. We should reduce the huge costs of work visas to ensure that we bring in the knowledge workers we need.

- Provide more funding for transport investment in towns and cities, especially the largest city-regions outside London, and for rapidly regenerating redundant industrial areas. Gradually devolving power over taxation and local investment would sharpen incentives for local government to rebuild cities – the more they improve land use and transport, the more tax revenue they will receive. Road pricing would help to alleviate congestion in the near term.

- Stop inhibiting the university sector with clampdowns on foreign students, row back on plans to tax universities for accepting them, and allow domestic tuition fees to rise with inflation. Universities are big sources of export earnings and key anchor institutions for many second and third-tier cities. The more they shrink, the more local economies will struggle.

- Complete the energy transition while managing the costs of investing in it. Fossil fuels and nuclear are not significantly cheaper than renewables, either financially or if the costs of pollution are included. Electric vehicles and heat pumps are already an upgrade on fossil-fuel technology. But imposing the costs of electrifying the economy on electricity bills is self-defeating. Move policy costs away from electricity bills, while spreading the extra transitional costs of upgrading the electricity grid over time.

- Rethink the investment and competition regime in services. There is little choice but to raise water bills to pay for investment, but stop using the failed retail price index as the basis for price increases. The policy of trying to get more companies to compete in contracted services has not worked well; too often, companies compete to extract rents by hiding charges in terms and conditions or segmenting markets so that less-savvy consumers pay more. Other forms of intervention are needed, such as mandating simpler products without hidden fees, and allowing consumers to get out of contracts more easily.

- Reform the tax system so that it does less to inhibit work, mobility and investment. National insurance contributions should be shifted onto income tax, so that the burden shifts towards non-labour income such as private pensions and rent. Council tax should be far more proportional to the value of the house. It is unjustifiable that a top-band house in Hull pays over twice the rate than Buckingham Palace’s nine residences. If stamp duty were abolished too, this regime would encourage housing to be used more efficiently, and help people move to places where they can get better jobs. Capital gains and income tax rates should be the same, to stop people from disguising their labour income as capital gains, but with an inflation allowance so that if they lose money on an investment they are not taxed.

This programme of reform is, of course, politically challenging. But Britain has stumbled along in a low-growth, low-wage equilibrium for a long time, and that has poisoned our politics. When economies don’t grow, politics becomes a zero-sum fight over distribution, with immigrants, poor people and other minorities becoming scapegoats for political failure. It will take luck and a good deal of political courage to turn the country around. But without action, things could easily get worse.

What has gone wrong?

Where has Britain gone wrong? There is general consensus about the malaise, but a cacophony of disagreement about the causes, ranging from the failures of the ‘neoliberal period’ on the left; the erosion of the Thatcherite settlement on the libertarian right, and the failure of self-dealing elites to ‘put Britons first’ on the radical right. Our answer is simpler: Britain has fallen out of love with the things it is good at, and in doing so it has undermined its advantages in the international economy.

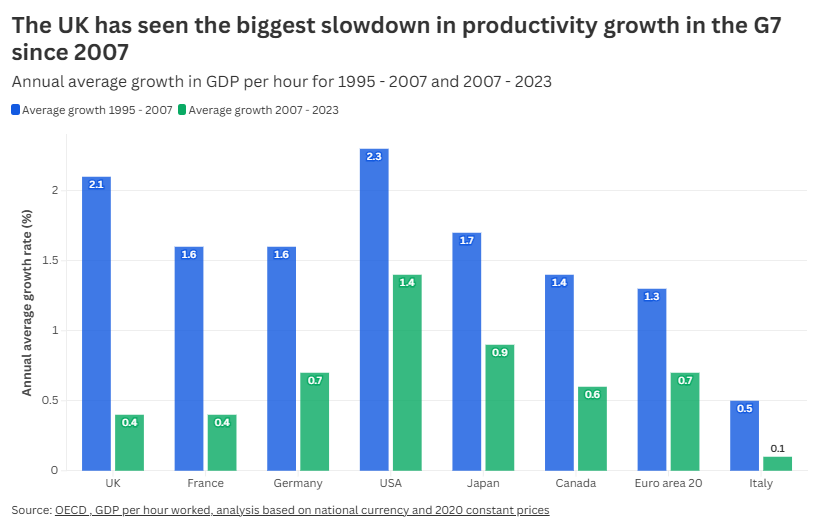

Productivity growth has slowed down in all advanced economies since the 2008 financial crisis, but it has been most abrupt in the UK. We argue that this has not been caused by anything fundamentally wrong with Britain or its economy; rather, it is the result of poor political decisions and an incoherent economic strategy. That should give some cause for optimism – while it will not be easy, cheap or quick to revive the UK economy, it is at least a tractable problem which can be tackled by making consistently good decisions. In some areas, moving power away from Whitehall would help to achieve greater consistency.

Our argument, at root, is that the UK’s problems stem from having too few successful, productive, international industries. This permeates all areas of national life. It means many places have too few well paid jobs and too little income coming in. This constrains spending in the local economy, hurting smaller businesses. Many town centres are dilapidated, for instance, because local people have too little income to spend in them. It also means that the government’s tax base is smaller than expected, which has ultimately led to a lack of public investment, a deteriorating public realm and declining public services, all exacerbated by an ageing population.

The economic force that the UK has got on the wrong side of is the ‘Baumol effect’. The New York University professor William Baumol found that wage rises in some industries – typically the productive, innovative industries – raised wages in all industries, including ones where productivity does not grow. While Baumol presented his thesis as a “disease” – because it means stagnant industries gradually take up a bigger share of the economy – we think it is mainly a force for good. If you can get a few key industries to innovate, grow and trade, you can pull up your whole economy. But in Britain’s case, its failure to grow its most successful industries has had the opposite effect; rather than pull the economy up, the magic of Baumol has dragged it down.

In a medium-sized, open economy, rising living standards depends on a vanguard of companies which, through better products and more efficient methods of producing them, earn revenues both here and abroad, which are then distributed across the economy. This distribution happens in two ways. The tax, welfare and public services systems shift money and resources to less productive people. But, more powerfully, the rising revenues of growing companies lead to higher wages, which then raises wages in lower productivity companies and the public sector – otherwise they would not be able to compete for the workers they need.

Why does the UK have too few successful, productive, international industries? There are many reasons, but the most important is that the UK has simply fallen out of love with the things it is good at. The things the UK excels at – finance and business services, tech and the creative economy, various advanced manufacturing niches – depend on openness: to trade, to ideas, to skilled workers.

In an open economy, competition from imports pushes British companies to pursue production niches in which they can earn the most, and open markets elsewhere provide them with more potential sales. And the flows of workers across borders – from a cleaner moving permanently to a Rolls-Royce engineer going on a business trip – allows Britain’s strength, the commercial services sector, to expand.

Top companies also rely on a range of underpinning infrastructure, from a world class university sector, to cities that work effectively as knowledge hubs, to effective and forward-looking regulation. In too many ways, the UK’s economic policies have worked against these goals, in both the short term and the long term.

Britain has been busily undermining its own business model. Brexit is the most obvious example. Another is its renewed attempt to curb migration after the post-pandemic surge. The government is focussing on work migration, because it’s easier to cut than family reunification. Foreign university students are treated as costs rather than sources of export earnings.

Another problem is the failure to expand successful places and regenerate struggling ones. Labour mobility within Britain has been declining as housing in productive regions has become scarce, which means that only the brightest and most advantaged can move to prosperous places in search of a better life. Many post-industrial towns and cities have been left to decay as their populations have grown, and their car-focused transport systems are often gridlocked. This has not made them attractive places for investment, either by Brits or foreigners.

Three big challenges add to the problems. The energy transition is going to get tougher, and policies to make it happen will become more intrusive. Getting to net zero requires a prolonged period of investment to decarbonise heat, transport, industry and food supply. That will largely be done by the private sector, but it will trim household consumption until we get to the other side, because energy bills will go up and households will have to invest in green technology, such as heat pumps and EVs, themselves. Russian aggression, the US retreat from Europe, and a more unstable, multi-polar world means that defence spending will rise, whoever is in power. Ageing societies – and richer ones – demand more public spending on health, pensions and education, which adds to fiscal pressures.

But all these problems are solveable. They imply a state which is larger, and in some areas, more intrusive, but much more efficient at raising revenue without damaging incentives for businesses and citizens. They entail a sustained period of investment in energy and the restructuring of Britain’s cities. They require Britain to remember that openness to foreign trade, investment, ideas and people is the bedrock of its prosperity.

This essay looks at five specific problems the UK faces in more detail. In turn, it deals with:

- Turning our back on trade and migration

- An economic geography that doesn’t match what we’re good at

- An energy system still stuck with gas

- A competition system that allows services to get more expensive

- A state that is losing the capacity to support the private-sector economy.

1. Making Brexit work: trade, migration and openness to the world

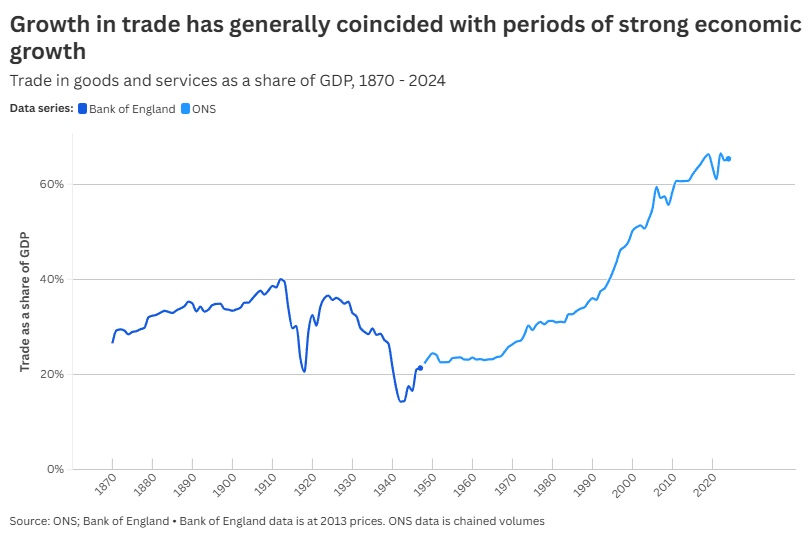

The UK has the 76th-largest land mass in the world, the 22nd-largest population and its economy is the 6th or the 10th largest, depending on how it’s measured. Small and medium-sized rich countries always do a lot of trading. A small land area means that many resources have to be imported from the tropics or more northerly climes, or countries with commodities that we don’t have, like coffee, wood, uranium and (increasingly) fossil fuels. As we have become richer there aren’t enough people willing to do the hard work of mining, clothes-making and fruit-picking in the country, so we pay people outside the country to do that work for us. Other rich countries have specialisms that we don’t have, so we import from them. In return, we sell the world products that require higher-tech machinery or niche skills. That virtuous cycle has made us rich, and a magnet for migrants looking for a better life.

As a result of the decision to leave the EU, Britain has tried to repudiate its history and violate one of the few consensuses of economics – that smaller, richer countries trade intensively, and that periods of peace, stability and economic growth tend to coincide with more trade. After the period of British global dominance ended in 1914, and over the course of the terrible first half of the 20th century, trade fell as a share of the economy. World wars, the collapses of the gold standard, the 1930s depression and decolonisation all contributed. But the stable post-war period, underpinned by US hegemony, helped Britain to become more open, contributing to its prosperity.

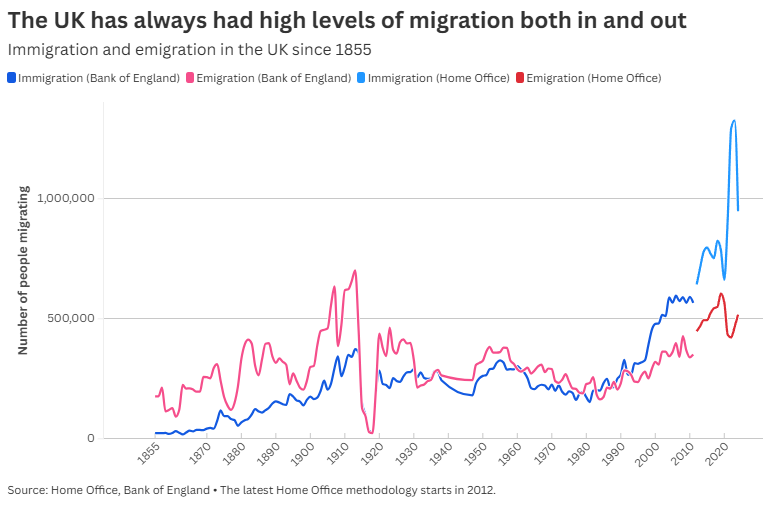

As well as being a trading nation, Britain has also been open to migration since the late 19th century, outside periods of war. Hundreds of thousands of people have left and entered the country each year since records began in the 1850s. What has changed since the 1980s is that the UK has flipped from being a country that sends more migrants overseas to one that receives them. While much of the focus of debate used to be on immigration’s effect on population growth, in recent years there has been a more pronounced ethno-nationalist edge, with right-wing politicians highlighting the shrinking share of ‘white British’ people, especially in London. But since around 1900 there was a fairly constant inflow of 200-300,000 people, many of whom were either not white or not British, so the recent rise is more a matter of scale than a departure from a homogenous norm.

Immigration raises growth, so long as most immigrants are employed, and employment rates among recent immigrants have been similar to British citizens. Wage growth has been rapid too. By tending to be young adults, Britain’s public finances benefit from immigration, since other countries have paid for their education, and they have decades in work before they retire and require more health spending. And while there isn’t a consensus in the economics literature about whether immigration makes existing residents richer – by bringing in skills or technology, or by taking on work that allows Britons to be more productive, for example – there is a strong consensus that it does not make them poorer.

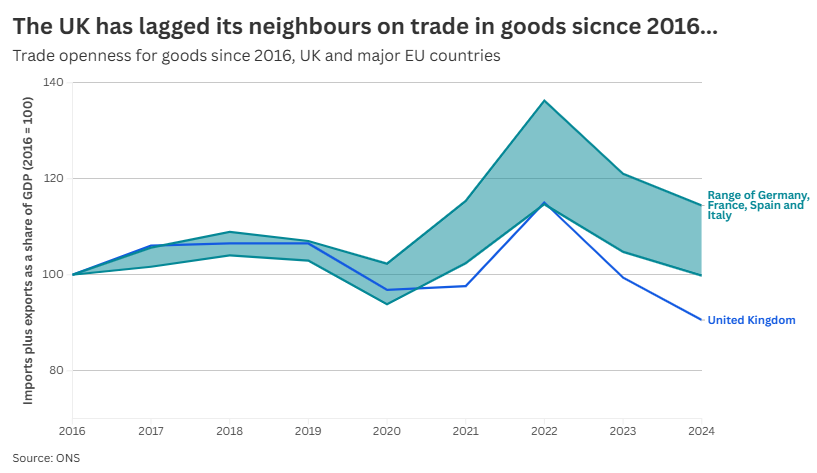

Since the Brexit referendum in 2016, the UK has become no more open to trade – with goods trade declining in real terms since the post-pandemic spike in 2022, offset by growth in services. Goods trade is now lower, as a share of GDP, than it was in 2019. By contrast, goods trade in peer economies in Europe is around the same level as it was before the pandemic struck. The retrenchment of goods trade has been offset by services, which have performed better than similar-sized European countries.

There is evidence that leaving the single market damaged services exports too – in finance and logistics especially. But services trade has been growing faster than goods trade across developed economies over the last two decades, driven by technological progress. More services can be delivered via the internet, making them more tradeable. This trend plays to the UK’s strengths in commercial services and tech.

But manufacturing matters, especially to towns outside Britain’s major cities, and it’s important to try to reduce the barriers to trade that Brexit has erected. As it is big, rich and right next door, any UK goods trade policy must have the EU at its centre.

Trade growth with distant countries cannot make up for Brexit losses. Trump’s chaotic trade policy, China’s turn towards import substitution since 2017, and the dysfunctional World Trade Organisation make a trade policy reliant on non-European markets a bad bet. As we discuss below, cities like London, Edinburgh, Bristol – and increasingly, Manchester – are well positioned to take advantage of growing services trade, but regional economies with manufacturing as their anchor, which tend to be poorer, are most harmed by Brexit and growing disorder in global goods trade. And it appears that, by cutting the UK out of European supply chains, Brexit is hampering manufacturing sales to the rest of the world.

Through its ‘Brexit reset’, the government is seeking to sand off the edges of the Johnson/Frost EU deal. If negotiations are successful, there will be better access to EU markets in agrifood, energy and the defence industry. But the largest Brexit costs are in manufacturing – especially cars, chemicals and industrial equipment. The UK desperately needs to re-establish its position in European supply chains in manufacturing, especially as Europe as a whole raises investment in clean energy and transport and boosts defence spending.

What should be done?

The ‘reset’ deal is the limit that can be achieved without accepting free movement and sizeable financial contributions to EU funds for poorer European regions. The EU’s mantra has always been that free movement and financial contributions are the responsibilities that come with the rights of single market participation. They have bent that principle, agreeing to negotiate single market participation in agrifood and energy for the UK formally aligning with EU rules in those areas, and to continue to update its laws as the EU rulebook changes. But applying the same method to the rest of the manufacturing sector will only be possible if Britain accepts the free movement of people.

The most committed people on either side of the Brexit divide would hate a new deal founded on the free movement of goods, energy and people. But there is much to recommend it. The UK’s strengths in services and tech mean that becoming a rule-taker in those areas would be challenging. In goods and energy, the UK is not going to regulate differently to the EU, not least because it is the country’s largest goods export market by far, but also because British regulatory preferences – on the environment, consumer safety and production standards – are very similar to the rest of Europe’s. Free movement flows have fallen back as wages in Central and Eastern Europe have converged with Western Europe, and unemployment has fallen in Southern Europe. Ukraine’s accession is some way off, and in any case transitional controls on free movement are likely once it does join. Since Brexit, the EU has found it easier to integrate in important ways without the British saying no, and there is limited appetite for the UK to rejoin; but UK participation in its goods market would help its manufacturers.

To get to a significantly closer EU relationship, Britain has to get over its neuralgia over immigration. But that will be important in the nearer term, too. At the peak of the post-pandemic surge in June 2023, net migration stood 900,000 people a year, but has since fallen back to around half that rate, and will almost certainly fall further. The measures in the government’s white paper on immigration will, if enacted, lead to further falls in immigration, especially of young skilled workers who will not meet the salary and qualifications threshold for a visa (around £40,000 and a degree-level qualification). The Home Office estimates that the measures will cut net migration by a further 100,000 a year, but migration forecasts are notoriously hard to do, and the government is as likely to miss on the downside as the upside. James Bowes, extrapolating from recent visa data, thinks net migration might fall to between 70,000-170,000 in 2026.

There are three reasons why continued net migration of between 200-300,000 a year – the normal range since 2004 – would be good for Britain’s economy. First, its strengths in high-skilled services mean that human capital, as much as physical, is at the heart of its growth model. As an innovator in tech, healthcare, energy, finance, law, accounting and culture, being open to skilled people in those areas is crucial. Second, Britain’s creaking infrastructure and ageing housing stock, especially in towns and cities that need to participate more in the international economy, are holding back growth. Building more will require a large amount of imported labour. Third, Britain’s ageing society means that immigration helps to keep public finances sustainable, and the NHS and the social care system have always disproportionately relied on foreign nationals.

It will take time, concerted effort and political courage to repair the UK’s position in the European manufacturing base. In the interim, the government can do more to make the UK an attractive place for skilled immigrants in tech, science and services. The first priority should be to reduce the cost of immigration, by reducing Britain’s visa fees and charges – which are by far the highest among rich countries. The cost of a UK ‘Global Talent Visa’, including the NHS surcharge, is nearly £6,000. The cost of an equivalent visa in Germany is £170, and in the US, £305. With the UK moving even more decisively towards a services-oriented, human-capital heavy economic model after Brexit, it needs to make it easier for people with skills and knowledge to come.

The UK’s history has been one of openness to trade and migration. The Brexit era has been a violation of that history, and unsurprisingly, it has reduced growth, and set Britons against one another. There is hope that voters may return to the country’s tradition of openness over time, as younger cohorts reject the right’s turn towards nativism. But so far, successive governments have been unwilling to take on the argument that must be won to assure broad-based prosperity.

2. Faulty economic geography: not matching places to the things we’re good at

Some of Britain’s economic problems go back much further than the 2010s, and chief among these deep-seated problems is a failure of its economic geography. Britain’s economic geography is not well matched to the things it is good at. Its cities – with the important exception of London – do not have the shape or the transport systems to support modern, service-led economies at a large enough scale. London is a different story, but it has not expanded as much as it should, and has seen its productivity growth stall since 2016. Meanwhile, smaller cities and towns across the rest of the country, which tend to rely more on making things or moving them around – manufacturing, food production, distribution centres, shipping and power generation – have also been neglected. These problems hurt many individual places, but they also hurt the UK economy as a whole: if your places don’t suit the things you’re good at, you’re unlikely to do enough of them.

There are broadly three types of economic place in Britain: London and its hinterland, which has a large and hugely successful service-based economy; larger city regions outside London, many of which have small successful service economies, but have larger manufacturing hinterlands which have declined; and all of the remaining cities, towns and rural areas, which tend to rely more on manufacturing, other forms of production and a mix of services, such as tourism and logistics.

London and its surrounding area have been the overwhelming success story of the British economy over recent decades. It remains one of the world’s leading centres for many global industries, particularly in finance, professional services and digital technology. It has extremely high skill levels, can attract people from all over the world, and has a good public transport system that enables it to function effectively as a very large labour market.

London’s success is partly historic – it has always been the UK’s dominant city and a global centre for finance and trade – but it has done especially well since the 1980s. The “big bang” relaxation of financial services regulation, along with the development of the digital economy, have helped London’s specialisms to expand dramatically. London also had a pre-existing public transport system, kept control of its buses during deregulation, and both became controlled by a city-wide mayor in 2000. The improvement in its air, water and schools, following the London Challenge, and large-scale regeneration efforts such as those at Canary Wharf, North Greenwich and Stratford also saw its population grow dramatically from the 1990s onwards, after decades of decline.

However, London has not expanded its footprint much in response to its success. This is partly down to the green belt policy imposed since the 1950s, along with limited investment in new towns outside London or major new transport links into the city. While expanding London might not help much with the city’s high housing costs – given the huge global demand for housing in London – it would very likely increase the nation’s prosperity.

But London’s problems are no longer just about space constraints and housing costs. London has also undergone a dramatic slowdown in productivity growth since 2016, despite having performed relatively well following the 2008 downturn. This partly reflects London’s struggles to remain a leading financial services sector following Brexit – one of the country’s most important industries being undercut by poor national economic policy.

For the larger city regions outside London – the likes of Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow, Leeds and Newcastle – the story has been very different. While most of these “second tier” cities have begun to reverse their decades of post-industrial decline, they still underperform vastly, both compared to their counterparts in other countries and their economic potential.

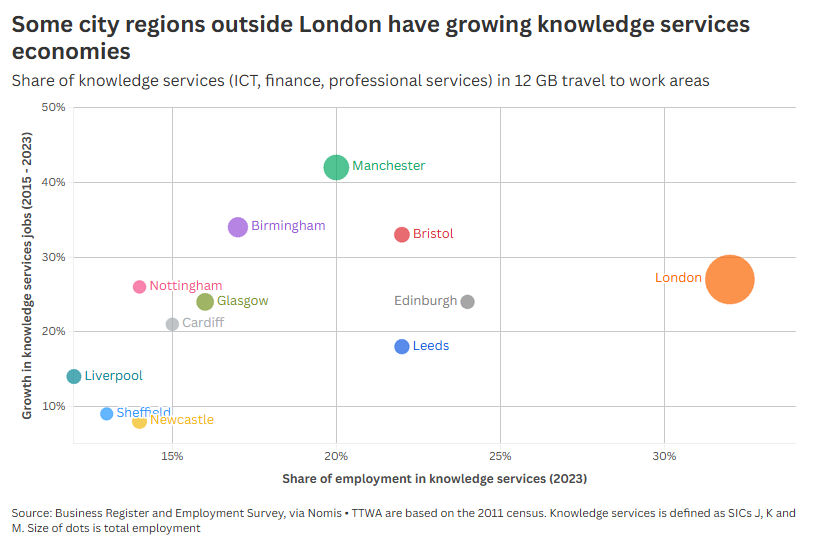

Many of these city regions outside London have growing knowledge service sectors – that is, the finance, professional services, science and tech industries in which the UK generally excels. Leeds, Edinburgh and Bristol have the largest shares of employment in these industries, while Birmingham and Manchester have seen more rapid growth in them than London since 2015. Other city regions, such as Sheffield, Newcastle and Liverpool, have much smaller knowledge service industries and have seen them grow less rapidly. These knowledge service clusters are normally based in city centres, rely on a high share of graduate workers, have high productivity and wages, and trade internationally.

Even in the more successful second tier cities, however, these knowledge-based clusters are still not large enough to make the city region as a whole successful. Bristol is the only one of England’s second tier cities that is more productive than the UK average. To make larger city regions like Birmingham and the West Midlands, Leeds and West Yorkshire or Greater Manchester prosperous, these city centre knowledge economies need to get bigger and higher value, enough to pull their whole city regions up with them.

For these cities to grow more quickly, they need to provide good, affordable city centre space, and they need above all else to attract skilled workers and companies that employ them. A key barrier is that – mainly because of poor transport and a lack of density – the pool of available workers in these cities is smaller than it should be, because too few people can commute to city centre jobs. Whereas London can draw on a huge pool of workers, and can attract people knowing that they will be able to find work, most other city regions have much smaller labour markets.

Much of this problem stems from weak transport systems, and from cities that have not been designed for modern, service-led economies. All of the large cities in the UK have a significant industrial heritage, which often means they are not as dense as they could be, and some land remains poorly utilised – sometimes even still derelict. Compounding this, public transport in cities outside London is generally poor, with privatised bus services and limited suburban rail and metro services. This creates more reliance on cars, which results in congestion and does not help expand the cities’ reach. As Anna Stansbury and colleagues showed, US cities tend to have decent access by road, and western European cities by public transport. Cities in the UK tend to have neither. While neither density nor decent transport are a magic fix for city economies on their own, it is much harder to build a strong, knowledge based urban economy without them.

Most other places in the UK, outside the major city regions and London’s hinterland, tend to have much less scope to build knowledge service economies. Instead, they rely more on producing things – food, manufactured goods, power or water – or services like tourism or logistics. Manufacturing remains very important in many non-urban economies, as a high value sector which still provides high value jobs, investment and exports.

The UK’s strengths in these sectors tend to be concentrated in niches, which rely heavily on international trade and on specialised local skills. However, many of these niche industries have seen limited support from government over time, not standing out as priorities for national governments which control most economic policy levers. Brexit has further hit many of these niches, introducing new barriers into often highly international industries.

The decline of such industries has hurt many smaller cities, towns and rural areas. When combined with shrinking local government, low public investment and stagnant public sector wages, it has helped to contribute to a sense of such places being “left behind”. While it is not always easy to rekindle economic growth in smaller cities that have experienced decline in their key industries, the government should encourage those industries that remain while giving places the tools to rebuild their economies.

Compounding the UK’s longstanding problems with its economic geography are two newer issues: the challenges facing the universities sector; and the higher cost of capital faced by firms outside London.

Almost every medium-sized UK city has a university. Universities are one of the UK’s greatest economic strengths, and they play a crucial role in supporting their local economies, both on the supply and demand side. However, many UK universities are facing financial crises and are reducing staff numbers. This is due to a combination of below inflation rises in tuition fees for domestic students and restrictions on international student numbers. International students are both very profitable for universities and a major UK export, but are being squeezed by political concerns over migration. A decline in the university sector would be a major setback for both the national economy and, more acutely, for many smaller local economies that have universities.

Since the financial crisis, businesses outside of London have faced a higher cost of capital, according to work by Phillip McCann and colleagues. This discrepancy may reflect less confidence in the economy outside London, or difficulties in valuing intangible capital effectively outside the London economy where financial services are clustered. Whatever the causes, this is likely to have significantly held back business growth in most of the UK, both in tech clusters in larger cities and in the production industries elsewhere.

What should be done?

First, Britain needs to direct more public investment towards remaking its towns and cities to fit their economic strengths. The case for more investment is most obvious in the more successful large city regions outside London, where it needs to focus on improving public transport and making better use of land, both for housing and employment. Doing so should make these cities functionally bigger, with access to larger labour markets and more opportunities. The priorities should be similar in smaller cities, with an emphasis on ensuring access to the affordable land, transport links and workers that make places attractive locations for businesses.

This extra investment must be tied, though, to a commitment to growth in the areas that receive it. Local governments should have both the freedom and the incentive to expand their areas. Local areas should have more freedom to plan, and more ability to keep the returns from land value uplift where development occurs. Alongside this, devolving more tax raising powers to local areas would ensure areas that grow receive more of the proceeds of growth. It is also crucial to ensure that local government has the day to day resources to be able to plan and think about growth and place making at all, rather than having to focus almost all funding on statutory services.

However, fiscal devolution is challenging to implement in a country that is so geographically unequal, and where local government capacity is limited in many places. A blanket approach to fiscal devolution, for instance, might greatly benefit the most prosperous parts of London. Instead, government should aim to gradually pass more and more tax raising powers to local areas. Simpler taxes such as tourism and parking levies, and business rate supplements would make a good first step. For those areas with the capacity to take it on, more significant fiscal devolution could follow.

Transport policy also needs to build on recent reforms. Bus franchising, the model that works well in London, has spread only very slowly to other city regions since 2017; the newly updated Bus Services Act should speed up progress on this. Local areas should have more freedom to build their own trams, light rail and metro systems, along with the resources to do so. And government should also aim to spread congestion charging to more cities, as part of a shift from traffic-heavy car transit to public mass transit.

Finally, national economic policy needs to pay far more attention to the industries that different places rely on. Turning around the university sector, by reducing restrictions on foreign students and finding a sustainable settlement on tuition fees, will help almost every local economy. Prioritising international access to financial and professional services markets will help London, but it will also help cities like Manchester, Leeds and Birmingham. If England can develop a second financial centre after London, this might help tackle the issue with higher capital costs for businesses outside the London ecosystem. Manufacturing, too, must not be neglected. Supporting the UK’s various manufacturing niches, both through specific and general policy, should remain high on the government’s agenda unless it wants to see further decline in many smaller towns and cities.

Economic geography is generally very slow to change, which means policy around it must be patient and consistent. That consistency is best achieved by setting up frameworks which give more agency to local areas to develop their own economies. That may lead to mistakes and failures in some areas, but the current Whitehall-led model has led to failures in most areas, so the case for change is strong. Greater Manchester, which has been a leading city in taking on more power from Whitehall, now appears to be one of the fastest growing parts of the country. The UK should be trying to repeat that story in as many different places as possible.

3. Energy choices: sticking with gas is expensive, cutting gas is expensive

Britain has what should be a short-term problem with energy, but one which is very acute. Its energy system is currently going through a difficult period, caught between investing heavily in clean energy and still relying heavily on expensive gas. But many of its problems should be transitional pains, rather than a sign that the UK is heading in entirely the wrong direction. Britain’s old energy system – relying on coal, oil and especially gas – has clearly run out of road, with its combination of high costs, high carbon emissions, dwindling domestic fossil fuel reserves and growing geopolitical risk.

The new energy system – based on very high investment but high efficiency and low running costs – is still in its early stages, and is not yet strong enough to shake off its reliance on gas. Many have diagnosed this as a failure of Britain’s direction and a reason to reverse course on net zero, or to switch to expensive alternatives, such as nuclear. This is precisely the wrong diagnosis, and would only extend the pain. Instead, Britain needs to complete its journey to a new energy system in as prompt and orderly a fashion as possible, while managing the costs of investment as carefully as possible.

Britain has been an early and consistent investor in renewable energy, which has helped it to more than halve its carbon emissions since 1990 and make it a global leader on climate change. Renewable energy, though, has run into some new challenges since 2022, with rising interest rates raising the cost of what is an exceptionally capital-intensive industry. The transition to clean electricity is defined by large upfront investments in return for much lower running costs – an equation that was much easier when interest rates were stuck at historically low levels.

Britain’s energy policy also suffers from its geography. Solar power, the runaway success of the clean energy revolution, is not quite as powerful in Britain as in more southerly countries, although it is still an important and cheap source of power. Britain has relied more heavily on wind power which, while it has also undergone dramatic cost reductions, is not as cheap and requires more capital investment than solar power. The rise in base interest rates, combined with policy errors creating a more uncertain environment for investors, has raised costs, especially for offshore wind. Being an island also means Britain is less connected to the larger European electricity market than most EU member-states, which draw on a larger and more diverse set of power sources.

The root of Britain’s energy problems, though, is its overreliance on gas. Oil and gas were a major source of economic growth in Britain from the 1970s through the 2000s, as exports from the North Sea swelled the country’s coffers and low gas prices helped make energy cheap and relatively uncontroversial. Gas has long been seen as the transitional fossil fuel as Britain decarbonised its electricity system, with responsive gas-fired power plants complementing renewable energy and enabling coal power to be phased out.

This has changed dramatically though: gas is now expensive, and the UK’s useful reserves are largely used up. But gas still plays a central role in the British energy system. It is piped into most homes for heating. That was the result of decisive policy, when Britain transitioned most homes from town gas, derived from coal, to natural gas between 1968 and 1976. Thanks to the importance of gas power plants, it sets the wholesale price of electricity most of the time. As the cost of gas has risen, Britain has been heavily exposed, with consequences for energy bills, economic growth and fiscal policy.

To add to this, many additional costs are being loaded on to electricity bills. A lot of the costs of supporting early renewable energy are still being paid for by today’s energy consumers. The switch to a renewable-led system requires additional investment in transmission and distribution infrastructure in advance of a big increase in electricity use; while this should be offset by much higher electricity consumption in the long term, in the short term it is increasing bills. Nuclear power, while often touted as a superior alternative to renewable energy, will significantly add to energy bills over the coming decades, as will technologies such as hydrogen and carbon capture and storage.

This loading of costs onto electricity bills is especially problematic, because Britain’s strategy relies on switching away from oil and gas and on to electricity. Electric vehicles may already have a big enough advantage over internal combustion vehicles to displace oil, but heat pumps need cheaper electricity to become an obvious replacement for gas boilers. Keeping the cost of electricity high will prolong Britain’s reliance on gas for heating, meaning higher bills, imports and carbon emissions for longer.

As well as hurting households and worsening the UK’s terms of trade, high energy bills have also affected businesses. Many other European countries, such as France and Germany, keep industrial energy bills considerably lower than consumer bills, while in Britain this gap is smaller. Despite some support for some energy-intensive firms, industrial energy bills in Britain have stayed higher than competitors since the 2022 energy crisis.

Britain does, though, have some relative advantages on energy and climate change. While it may not benefit from solar power to the extent that many countries will, its climate should remain relatively moderate compared to those at low latitudes. While climate change will have serious and deadly consequences in Britain, there is more scope to adapt to them, although this also requires urgent action.

Britain is also well placed to be a leader in energy services associated with running a low carbon energy system. As an early adopter of a zero carbon electricity system, with a challenging national grid to manage as well as a strong engineering services industry, the UK should be well placed to develop its expertise in this area.

Most of all, Britain is on broadly the right path in trying to increase its investment in renewable energy and grid infrastructure. In the same way that building the national grid in the 1950s and switching to North Sea gas from the late 1960s onwards represented decisive investments that paid off, the UK needs to complete its current course. Policy and operational reforms are still needed to make a low carbon electricity system work effectively, but the best way forward is to complete the transition Britain has started.

What should be done?

Although the government’s broad approach to energy is the right one, there are several ways in which it must improve its policy approach.

Perhaps the most important of these is to seek to lower the cost of capital for clean energy generation and electricity grid upgrades. Part of this is about lowering the risks involved in developing renewables projects through policy consistency. But the government could also use its balance sheet to lower capital costs more directly. It now has several vehicles – including GB Energy and the National Wealth Fund – which could do this, while basing the ‘falling debt’ fiscal rule on Public Sector Net Financial Liabilities should enable the government to underwrite more investment. Using these tools at scale could help to ease the costs of the energy transition without significantly affecting the government’s fiscal position.

The government must also follow through on its plan to make developing clean energy projects easier. Streamlining and reducing the uncertainties around grid connections and planning permissions should make new renewables cheaper and quicker to build. The state should lean in more to its role as an energy planner, ensuring that the right generation is built in the right place.

Next, the government should rethink its approach to loading costs onto electricity bills. Britain has one of the highest ratios between electricity and gas prices in Europe, which holds back the adoption of heat pumps and other electric technologies. This imbalance is driven in part by the many levies and costs that have been paid for via electricity bills. This both raises bills and sends exactly the wrong market signal for clean technologies, helping to prolong Britain’s reliance on gas. Shifting some of these costs from electricity to gas – perhaps via carbon taxation – is an option, although a politically challenging one. The Treasury should also consider taking some of the transitional costs of upgrading the electricity system onto the public balance sheet. It will be much better for future generations to have an upgraded energy system, lower carbon emissions and more debt than to have an energy transition that has fallen short.

The government should also begin rethinking its relationship with gas. Taking gas power stations – which will continue to be needed for filling gaps in the electricity supply – into public control could break the link between gas and electricity prices and should be considered. The state should also begin planning for the future of the gas grid, preparing to repurpose or wind down assets in an orderly, cost effective fashion. Carbon taxes on gas should also remain on the table, not least given the EU’s move to implement ETS2, which will impose a carbon price on consumer gas use.

While there is still plenty for the government to get right on energy, and plenty of pain to come in the short term, Britain’s long term strategy is still the right one. The challenge for government is managing the costs of investing in a new energy system while hastening the arrival of that new system as much as it can.

4. Inflation in the service sector: regulation that fails to curb price rises

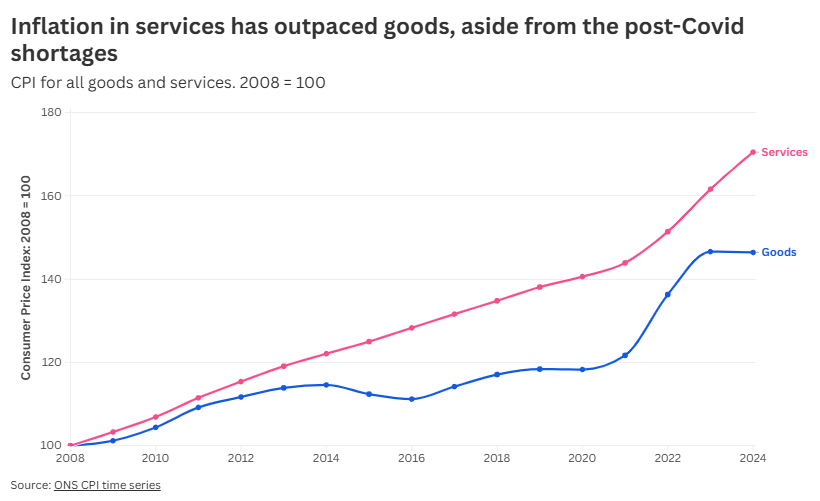

The UK has a long-standing problem with inflation in consumer services. Although the post-Covid burst of inflation was primarily driven by goods – especially essentials such as food and energy – it is inflation in services which has remained most persistent.

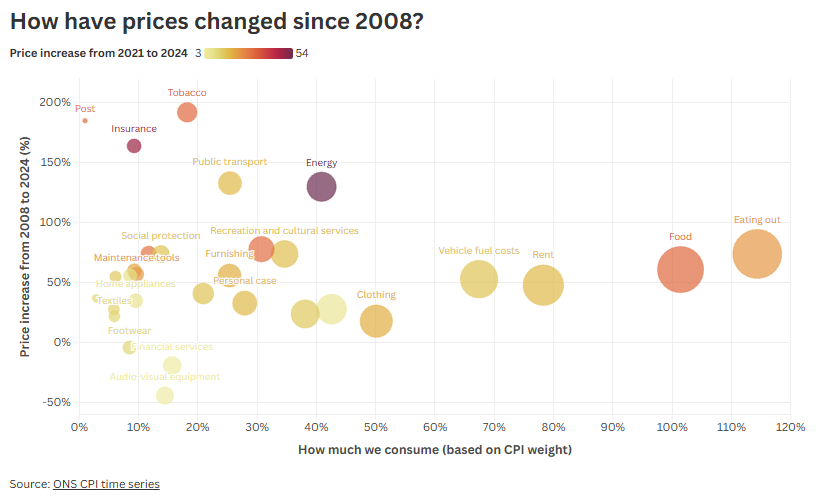

This is a problem, because services make up a larger share of the consumer basket than goods. These consumer services are generally not the productive, high value ones that Britain specialises in; those are mostly business-to-business services, which have not seen the same price rises. This means that many of the services that consumers spend their money on have become gradually more expensive than the leading sectors that help to raise productivity and wages across the economy.

Unlike goods inflation, which is often caused by global markets, geopolitics or climate change, services inflation is largely home grown. That means governments should be able to exert some control over it. The causes of consumer service inflation are likely to be varied. A classic explanation is that this is a manifestation of the Baumol effect: consumer services do not see productivity increase but do see wages rise, raising their relative cost over time.

But there are other possibilities that the UK needs to take seriously. For one, uncompetitive or poorly functioning markets, which lock consumers in to higher prices, can push up prices at above inflationary rates. For another, weak regulation, especially of utilities and natural monopolies, can lead to rising prices. The UK has been guilty of both failings in many markets, and has seen prices rise as a consequence.

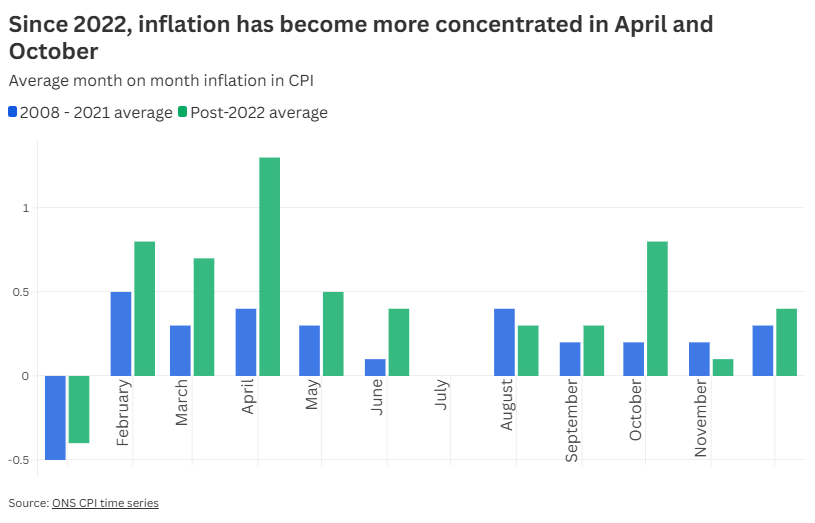

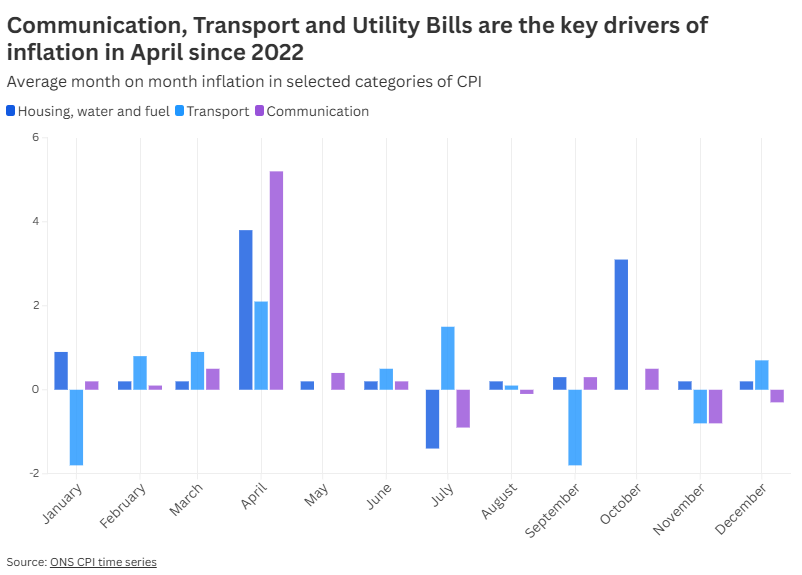

There are clues that this may be happening in the rise of “April inflation”. Since 2022, inflation has been much higher in the month of April relative to other months, and to a lesser extent in October too. April is typically a time where various bills – including utility bills and contracts – rise, sometimes due to contracts linked to the rate of inflation itself.

This April inflation problem is most concentrated in three types of goods and service: household bills; transport; and communication. These are all parts of the consumer basket that tend to either involve monthly bills or contracts, or to be regulated in some way.

Given this April inflation phenomenon, it is worth considering some of the markets that are driving this inflation. Many of these markets are either natural monopolies, or involve a high degree of state regulation:

- Public transport is made up primarily of natural monopolies, with a combination of private provision, state regulation and some government subsidy. Both rail and bus services have seen significant inflation since 2008, even though wages in the transport sector have not grown especially quickly.

- Telephone and internet services involve some competition, but have few infrastructure providers. This market also suffers from limited switching and from contracts where prices are set to rise above inflation every year.

- Water is a natural monopoly, which is privately provided (in England and Wales) but heavily regulated by the state, which sets prices and signs off investment plans. The 2010 to 2024 governments prioritised keeping bill rises down, but mistakes by the regulator and a failure to invest in sewerage infrastructure has led to steep bill rises at the same time as a downturn in water quality.

- Energy price rises have been dominated by the rise in gas prices and, to a lesser extent, investing in new zero. But the weakness of the regulated market has made the transition to a new energy system more difficult. A focus on competition as the main tool for protecting consumers has failed: it has created confusion over grid connections, and has mostly failed to prepare consumers for a more flexible energy market.

Aside from these “April inflation” markets, there are other services that have seen sustained inflation recently, which may have a more diverse range of causes. Accommodation and eating out, for example, are fairly competitive markets in which wage rises and limited productivity gains are likely to have been a major inflationary factor. The recent rise in food and energy costs will also have played a role.

Insurance, meanwhile, has seen dramatic inflation in recent years due to a combination of higher interest rates and rising claims (caused in part by climate change).

Some inflation in services is not, in itself, a bad thing, especially where it is accompanied by wage rises. The concern, though, is that too many markets for services are beset by problems with limited competition, ineffective regulation or problematic market structures that hurt consumers and make services inflation more persistent than it should be.

What should be done?

Britain’s problem with services inflation demands a response which is at once tougher and smarter. Regulation has increasingly failed to keep bill increases to a minimum, while competition policy has not stopped practices which are unfavourable to consumers from spreading.

There are two underlying issues that regulation and competition policy needs to address. First, there is a growing need to manage congestion in the use of many services and infrastructure. Many consumer services rely on infrastructure which has fixed capacity and high fixed costs. Being able to flex consumer demand to make best use of this infrastructure can reduce bills and lead to better outcomes. However, many consumer markets are poor at facilitating this kind of flexibility – sometimes because of overbearing regulation – which can lead to higher prices overall.

Second, there is often an information asymmetry between buyers and sellers in consumer markets, with sellers able to access large amounts of data on consumers to price discriminate or offer other unfavourable terms. Regulation and competition policy has in recent years focused on trying to correct this information asymmetry by providing more information to consumers and promoting choice and competition.

This has had mixed success: in markets where prices and quality are easily linked – for, say, consumer goods, competition has been good for consumers. The internet has also helped to improve the quality of restaurants and B&Bs, for example, through platforms that provide more information on choice (Google Maps and Airbnb) and provide consumer reviews. But in other markets, regulators have had less success, especially those that involve contracts of any sort, because most consumers don’t have the time or the skills to read the the terms and conditions, and producers have access to troves of data about how consumers behave in the real world, and can take advantage of them. Regulators need to look for other ways to protect time- and information-poor consumers without losing all the benefits of markets.

Many of the policies needed are specific to particular markets, and need to be designed at a market level. However, there are some general pro-consumer policies the UK government could consider implementing:

- There is a case for restricting the use of “RPI + x%” contracts, which uprate bills by more than inflation each year. Part of the basis for this is that RPI is a defective measure of inflation, and part of it is that these formulas progressively punish consumers who do not take action.

- The use of auto-renewing contracts could be limited, to prevent consumers stumbling into higher bills through inaction. While there are some cases – such as car insurance – where auto-renewal may be necessary, most services would benefit from clearer breaks in contracts.

- The UK government should implement a rule that anything you can subscribe to online can be cancelled online, without having to resort to a call centre or other time consuming process.

- Competition authorities should take a much firmer line against predatory pricing and business models that offer low initial costs that are designed to lock consumers in. Business models that rely on loss leaders to lock customers in are increasingly common and often harm consumers. While such cases always need to be weighed on their merits by competition authorities, they should lean towards much firmer action in such cases.

- Regulators might consider requiring providers to offer standard, approved products that provide a good deal to consumers, and allow providers to compete on price for them. Regulators could specify standard products – such as insurance products that work in almost all cases with a standard excess – to maintain competition on price but prevent insurers from hiding lots of exemptions in terms and conditions.

- In some markets, regulators may need to lean into encouraging flexible pricing, which would allow consumers to shift their use to periods when prices are lower. For example, requiring suppliers to offer a cheap overnight tariff and a heat pump-friendly tariff could help lower information consumers access the benefits of cheaper energy. EV drivers have already taken these up in droves, but many households could save by running their dishwashers and washing machines overnight on a cheap rate. The energy price cap could be extended to these products to provide consumers with protection from sudden price rises linked to the international gas market.

- In some cases, the state itself can provide consumers with a better deal. Road pricing is one way to do that. The UK has added seven million cars to the roads since 2000 – an increase of about a third. Congestion has large costs in the form of time that could be more productively used, pollution that makes people sicker and less likely to work, and burdens the NHS. The rise of EVs will help with pollution but they mean vehicle tax revenues will fall without reform. Dynamic road pricing, with higher prices at rush hours on congested major roads, policed via ANPR, would reduce commuter times, encourage people to travel outside peak times, promote healthier ways to get to work, and cut NHS costs. The charges could also be structured in a way that meant people who make most use of congested roads pay more (but get to their destination faster), while other drivers would be better off, compared to the current system of ‘free’ roads combined with vehicle taxation.

Regulating markets effectively is not an easy task and requires effective enforcement and specialist skills on the part of regulators. Accordingly, the UK government should aim to increase the capacity and remit of some regulators, such as the Competition and Markets Authority, while restoring regulatory capacity to local government. Spending a little more on effective regulation and competition policy could bring a big dividend for consumers.

5. Funding the state: raising state capacity while reforming the tax system

Underlying many of the failures of the UK economy is a decline in the capacity of the state to do things effectively. In many ways – such as the regulation of consumer services, provision of transport services or the state of the public realm – the British state has become threadbare and much less effective. This is both a consequence of and, in turn, a cause of slow economic growth.

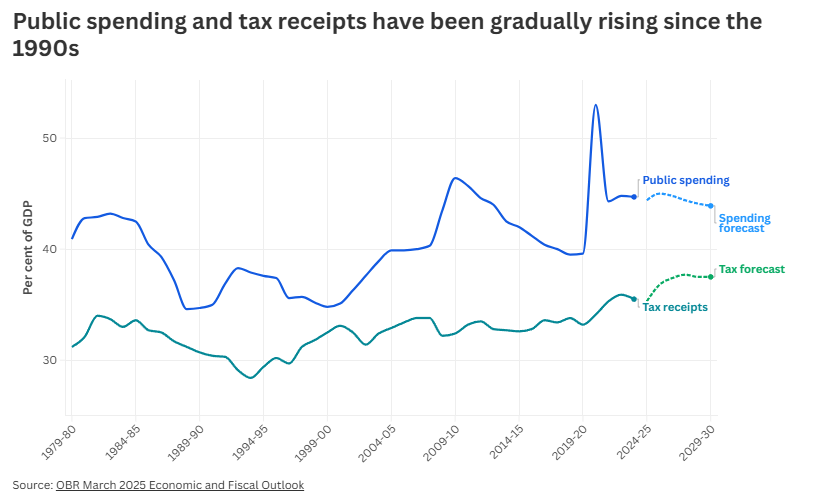

The decline in state capacity does not mean, however, that the state is costing less to run. The cost of the state has risen steadily, and bond markets are signalling that in the long term the UK needs to raise taxes, cut spending or both. This rise in cost is partly a function of underinvestment – state failures often create new costs for the state – but it is primarily a function of demographics. The UK population is getting older – a good thing – which means a greater share of our national income needs to go towards healthcare, pensions and other major areas of state spending.

At the same time, public investment will have to rise for the private sector to flourish. There is broad consensus that Britain has underinvested in transport, water and energy infrastructure. The resulting congestion has inhibited investment in the private sector, and made the UK less attractive to foreign direct investment. Given the Russia threat, defence spending will have to rise too.

The UK’s problem is not that its welfare state is too large or too generous, but that it has been in denial about the pressures of ageing and congestion. Ultimately, unless the UK government is prepared to stop doing things – such as providing less healthcare, education or defence – it will need to spend more money. Spending needs to rise to cover rising demands, but also to dramatically raise public investment and fund preventative measures that reduce spending in future. That means that, unless the UK economy stumbles upon a growth miracle, taxes need to rise.

There is much that could be written about the failures of the UK state, but this section concentrates on two issues: why we need to spend more; and how we can raise taxes in a fairer and more efficient way, so that the impact of higher taxation on private sector activity is minimised.

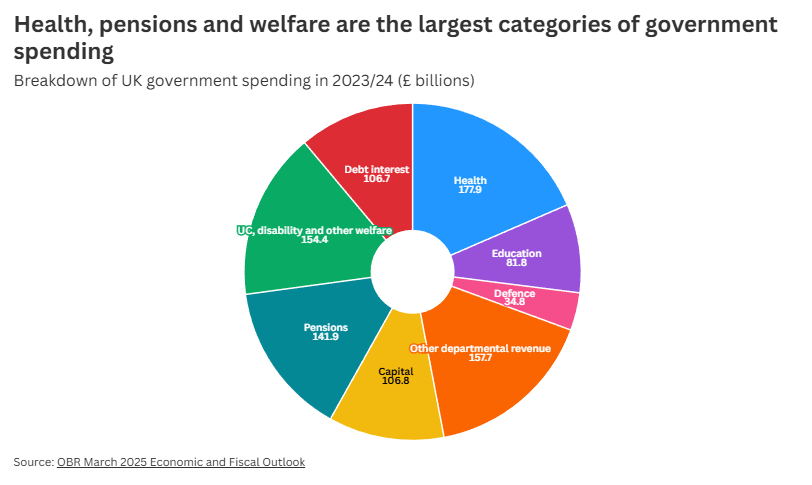

To make the case for higher spending, it is worth considering why many of the major areas of state spending cannot easily be cut.

Cut welfare spending?

Redistribution, the overall cost of the welfare system and work incentives are hard to juggle. To provide strong work incentives for people on benefits, government can taper them away slowly as people work more, so they don’t face high marginal tax rates. That requires more spending and higher taxes. Alternatively, government could cut benefits, in order to reduce costs, and spread benefits further across the income distribution to strengthen incentives to work more hours. But then poverty will rise because poor people who can’t or won’t work more, or progress their careers, will get less. There’s no escaping these trade-offs.

And there are a lot of people who are simply unable to work without benefits or benefits in kind – single, poorly paid parents with young children need free childcare in order to work; many disabled people have limited jobs they can do or can’t work at all. So Britain has to make difficult choices over poverty, work incentives, and benefit spending – it can’t wish these dilemmas away. That means that the welfare bill – which has been fairly static as a share of GDP for 35 years – is unlikely to come down much, whoever is in power. Britain has settled on a system that is pretty meagre by European standards but, by and large, protects people from the worst risks.

Cut the state pension?

The ‘triple lock’ – the state pension rising at whichever is highest of earnings, inflation or 2.5% – has been effective at reducing pensioner poverty. But there are questions about affordability, especially given the fact that it’s a universal benefit (if recipients have been in work for the required number of years). The rise in house values since the mid-1990s has also handed older owner-occupiers a big rise in wealth. And younger generations have not been saving enough for retirement, especially as wages have grown so slowly since 2008, so curbing the rise in the state pension entails a lot more pensioner poverty as they retire.

The state pension could be means-tested, but that would impose big risks to people who had ‘just enough’ pension savings. For example, interest rates could fall again, which would reduce annuity rates. The housing, bond or stock market might crash, cutting the value of assets. . So the government would be shifting risks to many individuals who might not be able to bear them. And when they retire government might well have to step in anyway if financial conditions wreck their retirement plans, because a high level of pensioner poverty has proved to be politically unacceptable.

None of this is to say that the state pension should continue to rise faster than working-age earnings indefinitely – or that the retirement age could be raised a little further. But the state cannot find large savings in this area as society ages – it can only trim the growth in spending on older people.

Make individuals take on more healthcare risks?

Similarly, shifting health risks onto individuals via insurance markets – as opposed to insuring against them through the state – would be unlikely to reduce costs. The UK gets middling health outcomes at a lower cost than most OECD countries, as measured by health spending as a share of GDP and relative longevity. State-run, or state-controlled insurance markets, typical in many other European countries, may get better health outcomes, but the probable reason is that funding is higher.

As the British population continues to age, spending on health will rise as a share of GDP: humans will pay a lot of money to prolong their life, and the efficiency and productivity of the health system cannot rise fast enough to offset those pressures. That is not to say that NHS reform cannot help -– more preventative care, faster diagnosis and more rapid care for a smaller increase in resources are obviously needed. In the short run, that would require higher spending, however, since investment in more efficient primary care and technology will be needed to raise productivity. That could be funded in part by co-payments for prescriptions and GP visits. But they are another form of tax, and would burden people in ill-health who may not be able to work.

Make individuals take on more social care risks?

Social care spending is rising because people are living longer, there are higher rates of diagnosis of conditions that require adult social care, and more premature babies are surviving into adulthood with conditions that require support. In England, the system is funded through council tax, direct grants to local authorities from central government, and by individuals. Only the most needy people – those without assets of £23,250 – qualify for state support. Even so, local authorities are struggling to meet demand, with a rising share of their budgets being spent on care, and most forecasts predict that spending will have to rise substantially in the future.

With one-in-seven people needing social care funding of more than £100,000 in their lifetime, it’s implausible that the state can retreat further from providing insurance against the risk of needing care. Repeated commissions have all recommended that the £23,250 threshold be raised, and tapered more slowly so that all adults with less than £100,000 in assets receive some state support. The latest, led by crossbench peer Louise Casey, is unlikely to recommend differently: the state is a sensible vehicle to insure against social care risks, because individuals can’t magic up higher assets to pay for it during their working lives, and many bet that ‘it won’t happen to them’.

The state should do less, better?

The state could retreat from other areas in order to focus on a few core missions, such as primary and secondary education, health and infrastructure. For example, it could:

- cut the prison population and use much more community sentencing, with more curfews and electronic tagging, and legalise and tax drugs to reduce police and criminal justice costs

- seek to free-ride on European defence by having smaller armed forces, and axing the nuclear deterrent

- further shift the costs of higher education onto individuals, by raising tuition fees or making graduates pay back more of their student loans

Some of these ideas have more merit than others and all have trade-offs. Cutting spending on criminal justice and police would entail more crime and disorder, and many countries have struggled to make drug legalisation work. Free-riding on European defence would make Britons less safe, given the threat from Russia, and the fact that the UK is a major contributor to the continent’s security. Shifting more costs of higher education onto individuals would mean fewer people going to university, which would reduce productivity and tax revenues.

As a result of these trade-offs, the hope that significant savings could be made is likely to be dashed. Across the OECD, the state’s share of the economy has been rising as economies mature and societies age. It appears that voters demand more from the state as economies become richer, because education and healthcare are more efficiently and fairly provided collectively. Education becomes more important because services-dominated economies reward higher skills, so voters want more of it. People will pay huge sums for another year of life. This suggests that taxes will have to rise further. It is vital that is done with the least amount of damage to the economy.

Tax reform

So far, the Labour government has been largely following the advice of Louis XIV’s finance minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, seeking to raise taxes, like plucking a goose, in order “to obtain the largest possible amount of feathers with the smallest possible amount of hissing”.

That’s because it promised not to raise rates of the big revenue raisers – income tax, employee national insurance contributions and VAT. It has used ‘fiscal drag’ – not raising income tax thresholds with inflation – in order to bring more people into higher income tax brackets. It has raised employer national insurance contributions and stamp duty on the purchase of second homes. And the ‘non-dom’ regime, which allows people to avoid tax on income they make outside the UK, will be abolished, and overseas income for UK residents will become liable for tax. Inheritance and capital gains tax exemptions and reliefs have been reduced.

Largely these tax reforms minimise hissing but, in some cases, curb employment and work incentives. Given the need to keep debt sustainable, the Chancellor is considering more tax rises – and, given the rising pressures on spending, the state is likely to continue to be larger than Britain has been used to.

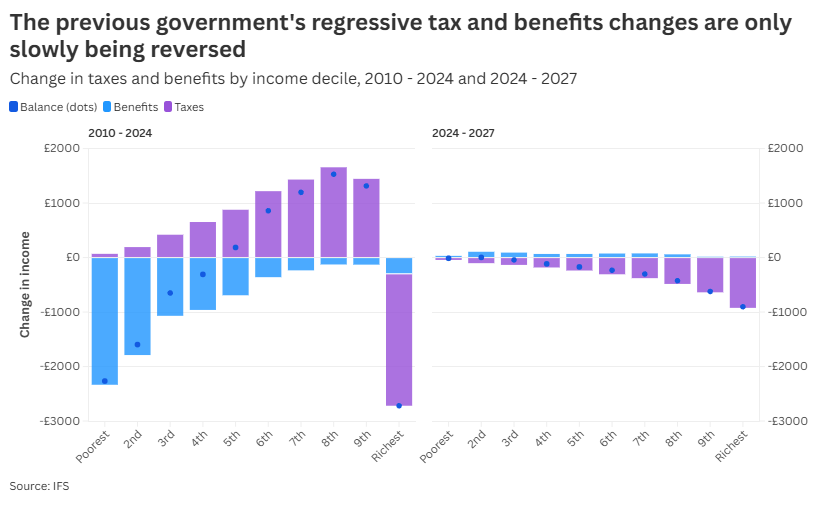

The tax and benefits changes announced by Labour since taking office will only mildly reverse the fiscal redistribution under Conservative governments between 2010 and 2024 – from households earning below median income, and the richest tenth of the population, to those in the rest of the upper half of the income distribution. Under the Conservative governments households in the 7th decile of earnings received £1,200, largely from tax cuts. Labour planned tax rises will cut their incomes by £300 by 2027.

Given the growing demand for public services, the threadbare state of the public realm, widespread child poverty and the country’s investment needs, the government has little choice but to reverse the tax giveaways to the upper half of the income distribution. It can do so in a way that does less harm to the economy than its strategy so far.

What should be done?

Income taxation

National insurance is a bad tax. Pensioners, the self-employed – and, surprisingly, partners in law firms – don’t have to pay it. So people who earn income by being employed by someone else are taxed at a higher rate than people who get income from wealth or who run their own businesses (or who can claim to do so). This is not only unfair – it also inhibits growth. Higher tax rates on employment reduce employment. Some workers decide to stay-self-employed, rather than working for a larger, more productive company. People are incentivised to retire early to reduce their tax.

The obvious answer is to abolish national insurance and raise income tax at an equivalent rate. This would simplify the tax system and strengthen work incentives. It would also raise substantial sums from people who don’t pay national insurance while enjoying high incomes. It would be bad for some poorer, self-employed people. But it would be progressive overall, because it would raise income tax on richer pensioners and self-employed people.

The reason why national insurance is so sticky, despite being so obviously distorting, is that Chancellors find it easier not to tackle the problem. Your national insurance does not pay for your state pension: the state pension is paid out of general taxation. Income tax rates are highly salient, with political storms whenever tax rates are raised by a penny or two, while national insurance is complicated.

As a result, the government should probably move step-by-step, reducing national insurance rates and raising income tax rates equivalently over time. There would be a lot of hissing, but if the government is serious about growth, this has to be the number one priority.

VAT

VAT is an efficient tax, raising a lot of revenue without creating too many frictions and bad incentives. It’s a tax on consumption, not production. Whenever a company sells a widget to another one, it pays no VAT, in effect: only the final consumer of the final good or service pays it. That means that, in general, it doesn’t penalise some producers and reward others, which would hold the economy below its potential output.

However, there are anomalies in the VAT system that do create these distortions. In part, that’s down to governments seeking to make the system more progressive. Since VAT is applied to consumption at a flat rate, people on higher incomes pay the same rate as poorer ones. To make VAT more progressive, there are lots of exemptions and lower rates for goods and services that we all need. Supermarket food is largely zero-rated for VAT. But it’s applied to hot food from a takeaway (but not cold food, as long as it’s consumed off the premises). VAT on energy is charged at a lower rate. All of these exemptions mean that richer people pay proportionately more VAT than poorer people, because they buy more VATable things. However, there’s no reason why healthy food bought in a restaurant should be subject to VAT when healthy food you’ve made yourself isn’t. Sugary and fatty ready meals are tax free, but kebabs aren’t, which hurts kebab shop owners and rewards supermarkets.

The other problem is that the VAT regime discourages business growth. The threshold before a business starts having to charge VAT is too high, at a turnover of £90,000. This is designed to give people an incentive to start businesses. But it is also, in effect, a tax on businesses growing. Unsurprisingly, there is a huge number of businesses, largely self-employed people, whose turnover is just below the threshold. Many people prefer to stay sole traders rather than taking on employees and apprentices.

The ivory-tower economist proposal is obvious – subject all goods and services to the standard VAT rate, lower the threshold, and offset the impact on poorer people by raising their benefits or reducing other taxes. This would be growth-supporting and maintain the current progressivity of the tax system as a whole. Again, tax politics is difficult, so moving stepwise to remove exemptions that serve little purpose and progressively lowering the threshold is probably the best strategy.

Property tax

The failures of the council tax system are well-known. The tax paid bears little relation to the value of the house, because it is based on valuations conducted in 1991. Since then, there has been a property price boom in London and the south-east, and in other rich parts of the country, resulting in ridiculous anomalies. The nine residences in Buckingham Palace pay £1,800 a year in council tax. They were in the top band in 1991, but pay little because Westminster council has very low council tax rates. A house in the top band in Hull, where residents are needier and the private sector weaker, pays £4,300. Westminster has lower expenditures than other councils because fewer vulnerable people live there and it receives large sums in business rates, the other main source of council funding.

Because council tax bears little relation to the value of the property, the housing stock is used less efficiently than it could be. Older people living in big houses in wealthy areas have little incentive to downsize, which inhibits housing supply for working families, and makes it difficult for people to move to areas where they could get a better job. This problem is compounded by stamp duty, a tax on buying a new home.